The family of Kotah, like that of Bundi, belongs to the Hada clan of the great Kshatriya Race of Chauhans. The Chauhans are not of the original ancient thirty-six Vedic Kshatriya races and are in no way connected with the Solar or Lunar Dynasties. They gained recognition late, around the 5th century AD. According to legend, they arose from the sacred fire-sacrifice performed by the sage Vahist eons ago in Mount Abu. Four mighty warriors arose from the pit of fire, each the progenitor of a clan: the Parmars, the Pratihars, the Solankis, and lastly the Chauhans. These four Rajput clans constitute the Agni Kul or the Fire Race. The Chauhans historically established themselves near Sakhambari near Sambhar lake, conquered Ajmer around 600 AD and forged a powerful kingdom which came to be known as Sapadalaksha, a vast expanse of land of 125,000 villages which comprised most of present-day Rajasthan, Haryana, the Punjab up to the river Beas, Delhi and the surrounding area of east Uttar Pradesh.

The high noon of the Chauhan Empire came at the time of the great warrior King Prithviraj, who was the last Hindu emperor to rule from Delhi. He was defeated by Sultan Moizuddin Mohammad-bin Sam of Ghor - better known to history as Mohammad Ghori – at the Battle of Tarain in 1192. After the fall of the Empire of Prithviraj, the main line sought shelter in the mountain fastness of the impregnable and famous fort of Ranthambor – now well-known for its tiger sanctuary. The other line established itself in Nadol, in the foothills of the Aravallis amidst the arid region of present-day Marwar. One off-shoot of the line called the Hadas migrated east and settled at Bambaoda, again in mountainous territory between Mewar and present-day Bundi. Soon they conquered the nearby areas of Mandalgarh, Menal, Bijoloan, Begoon, Rattangarh, and Bhainsrodgarh. They styled themselves Pathar Rajas but outwardly they acknowledged the overlordship of the powerful Ranas of Mewar.

In 1241, the Chauhan Rao Deva conquered the area of Bindo Nal from the Meena tribe and established his established his capital there, calling it Bundi. His rule extended eastward up to the river Chambal. The first to expand Hada rule across this river was Prince Jaitsi, the grandson of Rao Deva. He defeated the local Bhil tribal chief Koteya in 1264 AD, slaying him in battle. The severed head of Koteya was placed in the foundations of the new battlements being raised at the new brigand citadel, according to the time-honoured custom of offering nar-bali or human sacrifice when beginning such works. This new citadel and the nascent town which soon grew around it were named Kotah, deriving the name from the dead Bhil chief. A small shrine was erected where the mortal remains of Koteya were buried inside the citadel and where puja is still offered by the Royal Family from that day onwards. The pargana (district) of Kotah became the appanage of the crown princes of Bundi and remained so until 1624 AD, when Kotah was granted independent rule as a separate small kingdom to Madho Singh, the second son of Rao Rattan of Bundi.

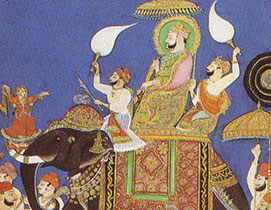

Rao Rattan was a grandee at the court of the Mughal Emperor Jehangir and Governor of Burhanpur when the imperial prince Khurram (later Emperor Shah Jahan) revolted against his father. It was Rao Rattan who crushed the revolt, captured Khurram and put him in prison in the fortress of Burhanpur. The actual work was done by Madho Singh, his second son, who was directly incharge of the royal prisoner. He accorded the royal prisoner full courteous and chivalrous treatment. In recognition of the great role played by Rao Rattan in crushing the revolt. Emperor Jehangir wished to reward him richly. Rao Rattan who was already in a position of great prestige and was held in esteem by the Emperor, Madho Singh was granted the independent rule of Kotah in 1624 AD. When Khurram became Emperor, after Jehangir’s death soon after, he did not forget the special treatment he had received at the hands of Madho Singh and was pleased to confirm the grant of Kotah. He awarded him special high honours, a khillat, (special order), and a sarapao, (a ceremonial robe), ratifying everything in 1631 AD.

Rao Madho Singh who ruled from 1624 to 1648 AD, was not only an able ruler but also a valiant commander. He was the first Hada Prince to serve under the Mughal Flag beyond Attock and the river Indus – the traditional boundaries of medieval Hindustan. He pursued and killed in single combat the rebel Afghan general Khan Jahan Lodhi near Kalinjar in 1631 AD. He later fought in Central Asia in Badakshan and served as Governor of Balkh.

He was succeeded by his eldest son Rao Mukund Singh (1648-1658 AD), another distinguished soldier. Mukund Singh was one of the few commanders who took part in all the three campaigns in Khandahar – twice under Prince Aurangzeb and once under Crown Prince Dara Shikoh. Near Kotah he built the fortifications of Darah Nal and also the small palace a top the hill for his beloved concubine Abi Meeni. This area with thick forests and hills 30 miles south of Kotah is today called Mukund-darah and has been famous for its wildlife. During the War of Succession in 1658 AD between the Imperial Forces and those of the rebellious princes Aurangzeb and Murad Baksh, a great battle was fought at Dharmat, also known as Fatehabad. The Imperial Army, under the command of Maharaja Jaswant Singh of Jodhpur, had as one of his commanders Rao Mukund Singh and his brave Hada warriors. In a gallant attempt to kill Prince Aurangzeb, Rao Mukund Singh spurred is horse to attack him on his elephant, but in this desperate act he was killed, along with four of his royal brothers who were all laid low on the field. Only the youngest, Kishore Singh, who was gravely wounded, was later carried away unconscious from the battlefield to ultimately reach Kotah.

Rao Mukund Singh was succeeded by his son Jagat Singh (1658-1683 AD), who also served in the Deccan and was killed in battle near present-day Hyderabad in 1683 AD. Since he died issueless, he was succeeded by his cousin Prem Singh, who proved to be incompetent and was deposed by the nobles within six months. Rao Kishore Singh (1683-1696 AD), a veteran warrior and the only brother to survive the Battle of Dharmat, was installed as the next ruler. He rose to be one of the important Mughal army commanders in the Deccan. He saw action against the kingdoms of Bijapur, Golkonda and fought at Arcot, Adoni, and Raigarh. For his gallantry he was awarded the royal nakkaras, (kettle-drums), by Emperor Aurangzeb. He later died fighting near Hyderabad in 1696 AD.

Rao Kishore Singh was succeeded by his younger son, Rao Ram Singh (1696 – 1707 AD), who was another distinguished soldier and renowned for his use of artillery. He conquered the territory of Rampura and Bhanpura in the south, adding to the Kotah territory and extending the Hada rule. In the War of Succession after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, it was a strange sight to see the scions of Kotah and Bundi, both Hadas, taking the sides of two Imperial Princes opposed to each other. Rao Ram Singh espoused the cause of Prince Azam who was defeated at the Battle of Jajav. Ram Singh sold his life dearly, fighting bravely first on his elephant, then when his elephant started to stampede, on his horse, and when the horse was shot beneath him, he stood his ground bravely on foot until he was finally killed. In the aftermath of this victory, Prince Muazzam, later the Emperor Bahadur Shah, gave the Bundi prince a free hand to subjugate Kotah. The Bundi forces besieged Kotah town, but Prince Bhim Singh, the young son of Rao Ram Singh, excelled himself by repulsing the Bundi troops. Hurt and stung by this treacherous act of his cousin from Bundi a lesson, subjugate and became the overlord of all the Hadas. Luck favoured him, for Bahadur Shah soon thereafter died, and in the political vacuum that followed and the murky politics which prevailed at that time in Delhi, there arose a powerful combine of king makers – the two Sayyed brothers (Sayyed Abdullah Khan Baraha and Syyed Hussain Ali Khan Baraha), joined by Maharaja Ajit Singh of Jodhpur. Bhim Singh soon became a valuable ally for them. This Sayyed Rajput combine proved very beneficial to Bhim Singh who shortly attained great power and prestige, which gave him a free hand to do what he had wanted to do. He was the first ruler of Kotah to be accorded the title of Maharao; he was raised in the Mughal mansab rank to 5,000 zat and 4000 sawar in 1716 AD, followed by the award of the royal dignity of the Order of the Mahi-o-Maeatib (one of the highest honours for Hindu prince) along with the royal nakkaras or kettle-drums in 1720 AD. He raided Bundi and brought it under his rule; he extended his dominion towards the south by grabbing the powerful fortress of Gagron and bringing Manoharthana Fort under his sway; and he extended Hada rule up to the river Narmada by adding Narsingarh and Rajgarh to his kingdom. Never in history had Kotah territory been so large and extensive. The prestige of Maharao Bhim Singh (reigned 17071920 AD) was at its highest at this time; he was also the first ruler of Kotah to embrace the cult of Ballabh Sampradya or Ballabh Kul.

This was also the point at which new interesting features developed in the Kotah school of miniature painting, the so-called Kotah qalam or school of painting – along with the Garuda insignia on the Kesaria or saffron-coloured State Flag, which clearly distinguished Kotah from Bundi.

Maharao Bhim Singh was a redoubtable warrior, seamed with battle scars. In 1720 he was ordered by the Mughal Emperor to assume command of an Imperial Force sent to block the progress of the Turani Noble Chin Kilich Khan Nizam-ul-Mulk (who later on became the first Nizam of Hyderabad, Asaf Jah I) who was proceeding to the Deccan against orders. At Pandher on the river Narbada a desperate battle was fought, in which ultimately the forces of Chin Kilich Khan emerged victorious. Maharao Bhim Singh had fought a heroic action and his body was retrieved from under a heap of dead Hada warriors, who had perished to save their king. The small golden idol of Sri Brijnathji, which the Maharao carried with him wherever he went, even in battle, was lost in the confusion of the battle. It was subsequently learnt that the Nizam had recovered it and given it for safekeeping and puja to a Hindu merchant. In 1724 AD, a deputation of Kotah Sirdars and officially was sent by Maharao Bhim Singh’s youngest son, Maharao Durjan Sal to Hyderabad to bring it back. The tutelary deity was received with full State Honours by Durjan Sal a good 50 miles out of Kotah, and brought back with great rejoicing and thanksgiving.

Maharao Arjun Singh (1720-1723 AD), who had succeeded Maharao Bhim Singh, died issueless. Thereafter, there was the grim spectacle of a short civil war between his two younger brothers, Shyam Singh and Durjan Sal. The latter emerged the victor, but in this fratricidal struggle Kotah lost the territories of Rampura and Bhanpura.

Maharao Durjan Sal who reigned from 1723-1756 AD was another great devotee and follower of the Ballabh Kul. He codified the puja, celebrated festivals of the Lord with befitting royal splendor, accorded great honour and reverence to the Presiding Deity and stood before it along with all his nobility and state officials as the first servant of the Lord. All these prescribed rituals, ceremonies and festivals with different codes of dress for each such occasion were prescribed, codified and faithfully followed until 1948 AD. The painters of Kotah richly recorded for posterity all this splendor in colorful pictures.

He also came to the aid of the dispossessed Bundi ruler, Umed Singh, who was thrown out by the machinations of the shrewd and powerful ruler of Jaipur, Maharaja Sawai Jal Singh. As a result Kotah had to suffer tribulation when the combined armies of Jaipur and Jai Appa Scindia besieged it for 62 days in 1745 AD. Inspired by the resolute spirit of Durjan Sal, the smaller Kotah Forces successfully defended the city and a lucky cannon shot from the citadel wounded Scindia in his camp across the river. This made the Marathas lose their appetite for a fight, and as a result the Jaipur forces also retired and Kotah remained unconquered.

Durjan Sal was an important prince at the Mughal Court. He was a devout Vaishnav Hindu and he exacted a boon from the Emperor against the slaughter of cattle in Delhi along the river Yamuna. He rescued a large herd of cows, maintained by the State until 1948.

Maharao Durjan Sal was also a great shikari or hunter. On his shikar he took along his royal ladies, who also shot. Thus one sees the famous hunting scenes of the Kotah qalam with royal ladies painted with exuberance and a wealth of details. Tod describes Durjan Sal as ‘a violent Prince and possessed of all the qualities of which a Rajput is enamoured, affability, generosity and bravery. He was devoted to field sports, especially the royal one of tiger hunting, had rumnas or preserves built in every corner of his dominions, some of immense extent with ditches and palisades and sometimes circumvallations, in all of which he erected hunting seats."

He was succeeded by his son Ajit Singh (1756-1764 AD) and later on by Ajit’s son Shatru Sal (1758-1764 AD.)

When Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh I of Jaipur received the sarkar (district) of Ranthambor from the Mughal Emperor, he tried to assert his overlordship over the eight Hada kotdies or principalities which originally came under this sarkar. These Hada kotdies were grants by the Mughal Emperor and ad quasi-independent status. They resented Jaipur’s efforts to exact tribute from them and so sought protection from the Hada States of Bundi and Kotah. As Kotah was bigger and more powerful, it offered protection, provided they acknowledge the Maharao as their suzerian and paid tribute to him. The kotdies agreed to this alliance and this became a cause celebre for the second clash of arms between Jaipur and Kotah in AD. The bigger Jaipur army was decisively beaten by a well-trained and compact Kotah army – under the inspired leadership of the young faujdar (officer) Zalim Singh. It was a crucial battle where the Kacchawas of Jaipur not only met ignominious defeat but also lost their claim to overlordship over the Hadas.

Shatru Sal I died issueless and was succeeded by his younger brother Guman Singh in 1766. A lynchpin in Mughal Administration. He had dual responsibility for making available military support (troops) and for running the revenue administration as well. When Guman Singh (1764-1770 AD) was dying, he entrusted the care of his son Umed Singh I, who was a young boy, to Zalim Singh whose sister was married to Maharao Guman Singh. Zalim Singh thus now became the Regent of Kotah. Already well known for his bravery as a soldier and skill as a faujdar, he now showed his shrewdness as a merchant-banker, his vision as a prodigious builder not only of public works, forts and fortifications but also of the power of the State. Kotah grew into a powerful and prosperous state and there was an air of settled peace about it. Zalim Singh established a gun foundry in Shergarh, a mint at Gagron and apart from numerous public works such as tanks, wells and storage for grain cut in rock, he also built the outer defence walls of Kotah City of a size and dimensions still quite unmatched in India; they are surpassed only by the famous Walls of Theodossius in Constantinople. The regent was astute enough to retain the full confidence and pleasure of his young royal nephew and ward, Maharao Umed Singh I. "No usurpation of power was ever more meek yet absolute". Remarks Tod.

The young Maharao who ruled from 1770 AD until 1819 AD, being freed from the burden of state affairs, had all the time in the world to devote to the princely sport of shikar, especially of big game which abounded in the rich forests of Kotah.

Up to now most of the rulers of Kotah were obliged to serve under the Mughal flag in Central Asia or increasingly in the Deccan. Five rulers had laid down their lives on the battlefield. Now there was no such call to duty. Umed Singh was a renowned shot, like his great grand-uncle Durjan Sal. He also built rumnas and shikargahs (hunting preserves), and encouraged his royal ladies to participate in shikar. He was a great patron of the fine arts and the blooming of the Kotah qalam in producing many of the finest shikar paintings, owes it to this fact. The strong wise rule of Zalim Singh and his skillful diplomacy kept Kotah free from the ravages of the Maratha hordes and the Pindari freebooters, making it stand out as an oasis of peace amongst the desolate wastes of loot, pillage and ruin all around it. In 1817 AD a treaty was signed with the Honorable East India Company whereby Kotah accepted the protection of the British, acknowledging their supremacy and agreeing to pay tribute which was hitherto being paid to the Marathas. One of the secret supplementary clauses of the treaty laid down that though the heirs of the Maharao would be rulers of Kotah state in perpetuity, the diwanshipor the administration of the state would rest for all times to come in Rajrana Zalim Singh and his direct descendants. This was a mischievous clause which led to trouble and discord in times to come.

The long 49-year reign of Maharao Umed Singh I came to an end in 1819 AD and along with it also ended the cordiality between the King and his Regent-Minister. The new Maharao, Kishore Singh (1819-1827 AD), was young and wanted to be his own master. This led to a head-on clash between him and the 80- year old diwan. The British mediated the situation and impressed on the Maharao that his position was purely titular according to the 1818 Treaty. But after a while there was a renewed clash and the Maharao left Kotah and sought shelter in ancestral Bundi only 22 miles away and later on went to Mathura on a pilgrimage. Undeterred, the old diwan Zalim Singh ruled Kotah by placing the khadaus, (the Maharao’s wooden sandals), on the gaddi (throne) – similarly as Bharat had done in the absence of Lord Rama, ages ago. But political manoeuverings and intrigues could not settle this fundamental and thorny issue. Soon the royalists in Kotah felt bold enough to challenge the authority of the old diwan. Zalim Singh sought the aid of British bayonets, and a brief but sharp battle took place at Mangrol in 1821 AD, close to the field of Bhatwara, where Zalim as a young Faujdar had first won his spurs and fame sixty years earlier in 1761 AD. The loyalists with their king were decisively beaten by Zalim Singh’s troops that were aided by a British regiment. Zalim Singh magnanimously declared an amnesty for all the loyalists, but the Maharao did not take kindly to this and sullenly went to Nathdwara in Mewar, where he remained at the shrine of Lord Srinathji. Zalim Singh who was blind had once again prevailed against all opposition in the twilight of his long and distinguished carrer. But this was to be his last hurrah, for he died soon after 1824 AD at the age of 84.

Maharao Kishore died three years later in 1827 and was succeeded by his nephew, Maharao Ram Singh (1827-1865 AD). Within a short while the simmering and unfinished quarrel broke out afresh in an open confrontation. The public sympathy lay as always with the ruler and an uprising against the diwan’s heir was feared. By now the British too had seen the utter impracticability of the supplementary secret clause and realized the awkward situation that had arisen out of the 1818 Treaty. They thus decided to put an end to this anomaly. Accordingly, with the consent of the Maharao, Kotah State was partitioned – giving seventeen nizamats (administrative units or tehsils) to a freshly created state of Jhalawar in 1838 AD. These nizamats plus four others, which were personally awarded by the British to Rajrana Zalim Singh for his help in suppressing the Pindaris, now constituted the sanad (treaty) State of Jhalawar.

The tribute paid by Kotah to the British was reduced but Kotah had to maintain an auxiliary military force called the Kotah Contingent, much against Maharao Ram Singh’s wishes.

Maharao Ram Singh was a ruler who also greatly patronized the Kotah painter’s workshops. He was fond of shikar, was ruler who enjoyed life with zest and had all episodes of his life, however whimsical, faithfully recorded and depicted by the Kotah artists. Hence one sees the second flowering of the Kotah qalam with same astonishing compositions. He attended the Durbar held at Ajmer by Lord William Bentinck in 1834 AD and also paid a visit to Delhi in 1841 AD.

The Great Indian Revolt of 1857 AD had its effect in Kotah too, when the troops of the Kotah Contingent also rebelled and attacked the British Residency, massacring the Political Agent Major Burton, along with his two sons and other officials. Maharao Ram Singh was besieged in the citadel, and the whole of Kotah City came under rebel control. It remained so from October 1857 AD until March 1858 AD. Help arrived in slow doses from loyal Rajput levies from the hinterland and a regiment of troops from Karauli State, where the Maharao’s son, Shatru Sal II, was married. Finally the British Rajputana Field Force from Nasirabad under Major General Henry Roberts arrived in late March 1858 AD. After a full day’s bombardment by British guns on rebel-held areas of the city, the combined forces went into attack and after some heavy fighting cleared Kotah city of all the rebels the following day, on 30 March 1858. The British force left Kotah City after occupying it for a month. As a mark of displeasure, the gun salute of Kotah was reduced from 17 to 13.

Maharao Ram Singh passed away in 1866 AD and was succeeded by his son Maharao Shatru Sal II (1866-1869 AD), during whose reign the gun salute was restored. He was a man of piety, addicted to drink, a recluse. Hence the affairs of state went into decline and apathy and mismanagement spread throughout the Kingdom. Soon matters reached such a point that Kotah State was in debt to the time of nearly Rs 80 lakhs (9 million). The state had an income of only Rs 30 lakhs – mostly through land revenue, and even this was not fully realized due to mismanagement. To set matters straight, the British Government of India appointed Nawab Faiz Ali Khan, an able administrator, as diwan. Soon the situation improved the debt was liquidated by 1885 AD, and the coffers in the state treasury started filling up again. The Maharao had no issue, but before he died in 1889 AD he adopted as his heir Udai Singh, the younger son of the Maharaja of Kotda, a kinsman and jagirdar, (feudatory lord), of the second rank. This was the wisest act that Maharao Shatru Sal II did, for this young village boy proved to the most benevolent and distinguished ruler Kotah had ever had, one who built Kotah up as a modern state, and one which was to become one of the most advanced and well-administered state of princely India.

On his becoming the sixteenth ruler of Kotah State in 1889 AD, the 16-year-old Udai Singh was named Maharao Umed Singh II. The events leading up to his adoption, his reaching Kotah secretly on the orders of the Maharao, the intrigues at the court, and his ultimate succession to the gaddi are a fascinating series of events which read stranger than fiction. Suffice it to say that it was a most fortunate event for the whole of the state and its people. He was to rule for the next 51 years. It is a curious fact that in the long 350-odd years rule of the House of Kotah, starting from 1624 AD and ending in 1948 AD, the combined rule of the two Maharaos called Umed Singh I and Umed Singh II total 100 years !

His reign started with a happy augury. On 1 January 1899 Kotah received back the 17 nizamats which had been carved out to be given in 1838 to create the State of Jhalawar. This restoration of nearly 2,500 square miles of territory made Kotah a big state once again, now measuring nearly 6,000 square miles. All this was possible because there had been an adoption of in Zalim’s direct line, which made a break in the line of descendants. The area of Kotah had been given to Jhalawar "for the direct heirs and successors"; the key words made all the difference now. A long and bitter legal battle was fought right up to the Privy Council in London, which ultimately decided in Kotah’s favor.

Maharao Sir Umed Singh II (1889-1940 AD) was a benevolent ruler, a good administrator and a warm-hearted person. With growing confidence, great dedication, and rare distinction. He gave Kotah a just and firm government, whose aim was to meet the needs of his people and keep them happy. He has also singularly lucky in having excellent officers under him, starting from his dedicated diwan, Sir Chaube Raghunath Das, downwards. Corruption was next to nil, and the revenue bandobast, (revenue system), on which the lot of farmers depended was thoroughly overhauled. This bandobast became an example for all - it was better than what was prevailing in British India. Many rulers of bid states came for their administrative training to Kotah to learn the art of governance. Kotah was the first state to use Hindi as its State language, one of the first to have a municipality whose first Chairman was the Maharao himself and the first state to have a co-operative movement. The Maharao built many public works and projects like tanks, lakes and irrigation canals for the good of the people and opened up the countryside with modern roads and bridges. Schools were built in all nixamats and big towns, education was free. All the beautiful modern buildings in Kotah City, from colleges, hospitals and government offices to the army area with barracks, were built during his reign. The new Umed Bhawan Palace was built in 1905.

Kotah was one of the earliest places which had a modern waterworks with a filtration plant that supplied safe water in abundance to the whole of the city, and this plant continued to do so until the early 1950s. Electricity and railroads also came during his reign. The Maharao undertook annual inspection tours of his state, camping approximately every fifteen miles, looking into the grievances of the common man, dispensing justice at once. Even the poorest or the most humble of his people could approach him directly, stop his flagged automobile and relate his grievance face to face. He aided and donated generously. The Benares Hindu University was one recipient where his name even name now commands respect. All told, his rule is remembered affectionately by the people of Kotah as the golden era in its history.

Maharao Sir Umed Singh II was educated at Mayo College, received his military training at Mhow, and became in due course one of the most distinguished and respected rulers of his era. He received high honours and dignities and was widely held in esteem. At the time of his death Kotah was a prosperous state, having an income of Rs 60 lakhs (6 million). He passed away in December 1940 at the age of 67.

His only child, Maharao Sir Bhim Singh II (b. 1909 AD - Ruled 1940-1948 AD) succeeded him and ruled until 1948 when Kotah State was merged into the newly-formed state of Rajasthan. He was responsible for creating an aerodrome, giving further impetus to modernization and for initiating a scheme to harness the hydro-power potential of the river Chambal which ultimately was developed and inaugurated in 1960 AD. He went overseas in 1944 AD during World War II, to inspect the Kotah First Umed Infantry which was serving in the Persian and Iraqi War Theatre. In 1948 Kotah State had an income of Rs 1.25 crore (Rs 12.5 million) and left over Rs 2.5 crores (Rs 25 million) in cash for the successor government of Rajasthan, which many bigger states did not. He became the Senior Up-Rajpramukh, (the deputy governor) of Rajasthan and served until 1956 AD. He also served in the UN General Assembly as an alternate delegate of India in 1955-1956 AD.

He was a keen shikari, a good photographer and deeply interested in the conservation of wild life. He gave up his personal game reserves in order that they could be turned into a Wild Life Sanctuary and he later became the first Chairman of the Board for Conservation of Wild Life in Rajasthan. He took to clay- pigeon shooting and was the National Champion in Skeet for quite a few years. He represented India in many international competitions abroad and was the oldest competitor at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. For his commendable performance in Skeet shooting he received the prestigious Arjuna Award – the highest a sportsman can get in India. Educated at Mayo College, he served for twenty-five years as its Chairman. He was an enlightened ruler, a perfect gentleman, soft-spoken and kind. He was deeply respected by his people. He passed away at the age of 81 in 1991 AD.

Maharao Bhim Singh was succeeded by his only son, Brijraj Singh, who is the present Head of the Family. Born in 1934 AD, Maharao Brijraj Singh also received his education at Mayo College and later at Delhi University. He went into politics and served for three consecutive terms, from 1962 to 1977, as an elected Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha). He also served as the Chairman of the prestigious Mayo College for 10 years. He is widely travelled and leads a retired life now. He has written a book called "The Kingdom that was Kotah" on the Kotah qalam of Indian Miniatures and is deeply interested in history and art.

His only son, Ijyaraj Singh, was born in 1965 AD. Following the family tradition, he is the fourth generation to be educated at Mayo College; he attended Brown University in the USA, from where he graduated with distinction in B.Sc. and later completed his MBA from Columbia University, New York, again receiving distinction and mention in the Dean’s list. He worked for a few years with the BASF Company in Germany and England and later joined the Deutsche Bank in Delhi. He is now in Kotah looking after the family estate and business. He has a son, Jaidev Singh, born in 1997. He was recently elected the MP from Kota-Bundi seat in 2009 with a large margin.

By the grace of God, the House of Kotah is destined to carry on well into the next century, to keep up the good work it has had the privilege of doing in all these past centuries.